Ten Books That Shaped the British Empire: Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management

Last week WiSER hosted the Johannesburg launch of Antoinette Burton and Isabel Hofmeyr‘s new edited collection Ten Books That Shaped the British Empire: Creating an Imperial Commons. Isabel invited three historians to pitch the books that they feel should have been included, and it was the funniest and most entertaining launch I’ve ever attended – and had the honour of speaking at. You must, of course, read Ten Books. It is that rare thing: an academically rigorous text which is accessible without losing any of the complexity of its arguments.

I picked Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. This is what I argued:

I picked Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management. This is what I argued:

I nominate a book which has been accused not only of dooming British cooking to a repertoire which makes a virtue of stewed tea, turnips, and something called toast water – no, me neither – but whose author was labelled by Elizabeth David – no less – a plagiarist. David added: ‘I wonder if I would have ever learned to cook at all if I had been given a routine Mrs Beeton to learn from.’ I argue that Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management – or, to give it its full title, The Book of Household Management, comprising information for the Mistress, Housekeeper, Cook, Kitchen-Maid, Butler, Footman, Coachman, Valet, Upper and Under House-Maids, Lady’s-Maid, Maid-of-all-Work, Laundry-Maid, Nurse and Nurse-Maid, Monthly Wet and Sick Nurses, etc. etc. – also Sanitary, Medical, & Legal Memoranda: with a History of the Origin, Properties, and Uses of all Things Connected with Home Life and Comfort – was one of the most important and influential books to circulate around the British Empire. It shaped both the colonial encounter, and the postcolonial kitchen.

This is not so much a history of a book, but a history of a compendium of advice assembled, edited, and changed over time, originally by a woman and her husband, and then by an assortment of publishers and printers. Isabella Beeton was twenty-one years old and newly married when she began publishing articles on cooking and domestic advice in The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine. In 1861, she published what was possibly the world’s first serial recipe book – her guide to household management – and it promptly sold out. Mrs Beeton sold 60,000 copies in its first year, and 2 million by 1868. It is still in print. But by 1868, Isabella Beeton had been dead for three years – and probably as a result of complications arising of syphilis, which she had caught from her philandering husband, Samuel.

As death was the most useful thing to happen to John F. Kennedy’s career as the best president the US never had, so Isabella Beeton’s early demise helped to transform her book from a, to the guide to respectable living for the middle classes. Samuel Beeton was the book’s publisher, and as readers clamoured for yet another updated edition of Mrs Beeton – and he remained deliberately vague as to where the real Mrs Beeton really was – the book was corrected and modified to suit the changing circumstances of nineteenth-century middle-class households.

Mrs Beeton was not the first or the best recipe book of the period – Eliza Acton and before her Hannah Glasse were more accomplished cooks – nor was Isabella the first author to compile her book from snippets and cuttings from other sources. Mrs Beeton was always a compendium, a scrapbook. But this book was the first to give cooking times, accurate lists of ingredients, and menus arranged by cost. This was a practical guide to living for Britain’s new middle classes, which demystified table settings, etiquette, laundry, the management of servants, and the everyday rhythms of a respectable households. Also, this book worked to empower middle-class women, providing them with a range of skills – bookkeeping, nursing, project managing – that their daughters would use as they began gradually to enter to the workplace during the early decades of the twentieth century.

Young women packed Mrs Beeton into their luggage and sailed with her around the empire, and so Mrs Beeton also became the foundation on which middle-class British households were made in regions as far a flung as Nigeria and Australia. But Mrs Beeton also became a metaphor for the British Empire during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries: endlessly mutable, able to change according to circumstance, meaning many things to all people at once. Linked to another saintly, if distant female figure, this book was both emblematic of a well-run household as well as a canny business machine.

Gradually, foreign recipes – for mulligatawny soup from India, lamingtons from Australia – made their way into the book. But in the colonies, Mrs Beeton became the basis for local guides to household management. In South Africa, the wildly popular Hilda’s Where Is It? by Hildagonda Duckitt (1919) and even Kook en Geniet (1951) were both obviously modelled on Mrs Beeton. In fact, Kook en Geniet could best be described as the Afrikaans Mrs Beeton. Published as a guide to housekeeping and cooking for young brides in 1951 by Ina de Villiers – and overseen by her daughter Eunice van der Berg since 2010 – it has never been out of print. Like Mrs Beeton, its success lies partly in the fact that it is regularly updated. There is no single version of Kook en Geniet. Each edition retains a core of essential recipes, but methods and ingredients change as new products appear. Dishes are added and, less frequently, subtracted as culinary fashions evolve.

Mrs Beeton was also the model for guides to colonial living. The Kenya Settlers’ Cookery Book and Household Guide, published by the Church of Scotland’s Women’s Guild in 1943, walks an uneasy path between demonstrating to young wives how to maintain the standards of Home, but also providing practical advice as to keeping house in east Africa. This is a guidebook in aid of civilisation: while some concessions are made to Kenyan conditions, its model remains always Mrs Beeton. Its recipes are for macaroni cheese, chicken pie, and shortbread. Gardens are to be planted with poppies, dahlias, roses, carnations, and snapdragons. African servants are to be civilised. Phrases in Swahili and Kikuyu centre around cleanliness, punctuality, and obedience. Even African chickens had to trained into good behaviour. When local ingredients – like mangoes or maize meal – were used, it was in the context of familiar recipes: green mielies au gratin, boiled banana pudding.

Mrs Beeton was also the model for guides to colonial living. The Kenya Settlers’ Cookery Book and Household Guide, published by the Church of Scotland’s Women’s Guild in 1943, walks an uneasy path between demonstrating to young wives how to maintain the standards of Home, but also providing practical advice as to keeping house in east Africa. This is a guidebook in aid of civilisation: while some concessions are made to Kenyan conditions, its model remains always Mrs Beeton. Its recipes are for macaroni cheese, chicken pie, and shortbread. Gardens are to be planted with poppies, dahlias, roses, carnations, and snapdragons. African servants are to be civilised. Phrases in Swahili and Kikuyu centre around cleanliness, punctuality, and obedience. Even African chickens had to trained into good behaviour. When local ingredients – like mangoes or maize meal – were used, it was in the context of familiar recipes: green mielies au gratin, boiled banana pudding.

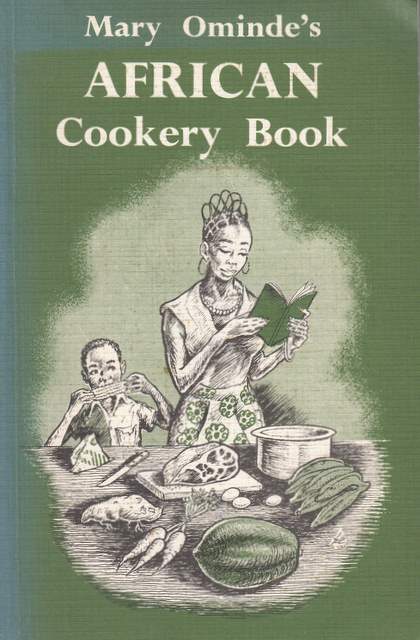

But Mrs Beeton’s influence didn’t vanish with the end of empire. She is present, too, in postcolonial recipe books. Mary Ominde’s African Cookery Book, published by Heinemann in 1975, is intended for housewives in independent Kenya, eager to play their role in raising healthy Kenyan families. But it is based very obviously on earlier colonial guidebooks. It – too – has borrowed or plagiarised from other writers, and while it does include some local recipes, for nyoyo and blood in sour milk, its emphasis is overwhelmingly on cooking dishes familiar to readers of the Kenya Settlers’ Guide. But this – like Kook en Geniet – is a recipe book in service of nationalism.

But Mrs Beeton’s influence didn’t vanish with the end of empire. She is present, too, in postcolonial recipe books. Mary Ominde’s African Cookery Book, published by Heinemann in 1975, is intended for housewives in independent Kenya, eager to play their role in raising healthy Kenyan families. But it is based very obviously on earlier colonial guidebooks. It – too – has borrowed or plagiarised from other writers, and while it does include some local recipes, for nyoyo and blood in sour milk, its emphasis is overwhelmingly on cooking dishes familiar to readers of the Kenya Settlers’ Guide. But this – like Kook en Geniet – is a recipe book in service of nationalism.

Mrs Beeton was, then, essential to the shaping of the colonial encounter between white women and children and African and Indian servants. She provided its domestic framework – a model of the ideal home at Home in Britain – and local writers created guidelines for the achievement of this manifestation of order and civilisation in the colonies. She persisted even after the end of empire. Postcolonial recipe books were informed not only by the structure of Mrs Beeton, but also the book’s recipes and ethos. Building a nation through food, if you will.

Tangerine and Cinnamon by Sarah Duff is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Tangerine and Cinnamon by Sarah Duff is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.