Starved Out

Two years ago today, police opened fire on a group of striking mineworkers encamped on a koppie outside of Marikana. Mainly rock drill operators doing some of the most basic and difficult work on the mine, these men demanded that Lonmin – in whose platinum mine they worked – raise their salary to match that of literate, better skilled miners, to about R12,500 per month.

After weeks of sporadic violence on both sides – during which policemen, shop stewards, and workers were injured and killed – mine bosses urged the police to end the standoff. Jack Shenker writes:

It was the police who escalated the standoff at Marikana mountain, bringing in large numbers of reinforcements and live ammunition. Four mortuary vans were summoned before a single shot had been fired. Lonmin was liaising closely with state police, lending them the company’s own private security staff and helicopters, and ferrying in police units on corporate buses. Razor wire was rolled out by police around the outcrop to cut the miners off from Nkaneng settlement; pleas by strike leaders for a gap to be left open so that workers could depart peacefully to their homes were ignored.

Police opened fire as workers approached them. In the end, thirty-four were killed, seventeen of them at a nearby koppie where it appears that they were shot at close range. The Marikana massacre has been described as post-apartheid South Africa’s Sharpeville. As the inquiry into the events near the mine has revealed, police arrived not to keep order, but, rather, to end the strike through any means possible.

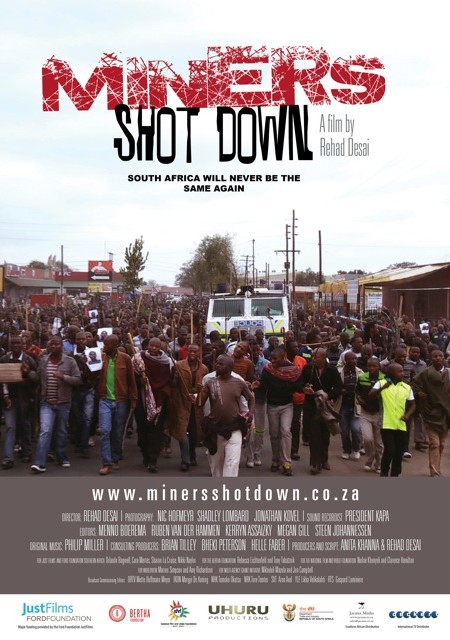

The poster for Rehad Desai’s documentary on the Marikana massacre, Miners Shot Down.

The killings were followed by a strike – the longest in South African history – until May. Of all the details to emerge in the coverage of life in the platinum belt, the one that seemed to encapsulate the desperation of striking miners and their families was in a 2006 report commissioned by Lonmin: researchers had discovered children suffering from kwashiorkor near the mine.

Although already identified in 1908, kwashiorkor was named by Dr Cicely Williams, a Colonial Medical Officer, in the Gold Cost during the 1930s. Tom Scott-Smith explains:

she noticed a recurring set of symptoms amongst children who were aged between one and four: oedema in the hands and feet, darkening and thickening of the skin followed by peeling, and a reddish tinge to the hair in the worst cases. There was a clear pattern in the incidence of this disease, since it occurred in children who had been weaned onto low-protein, starchy foods such as maize, after being displaced from the breast by a younger sibling. Williams’ description first appeared in print in 1933, and two years later she identified the condition by its name in the local language: kwashiorkor, the ‘disease of the deposed child’.

Williams diagnosed kwashiorkor as a from of inadequate nutrition – similar to pellagra, which is caused by a diet insufficient in vitamin B3 – related specifically to an intake of too little protein. Williams had noticed that newly weaned babies and young children – the ‘deposed’ children referred to by the word kwashiorkor – were particularly vulnerable to the condition, and surmised that longer breastfeeding or a diet rich in the nutrients non-breastfed children lacked – protein especially – would eradicate kwashiorkor.

By the 1970s, though, doctors argued that this emphasis on protein supplements – which had driven United Nations and other organisations’ efforts to address kwashiorkor – was incorrect. Kwashiorkor, they argued, was the product of under nutrition: of not consuming enough energy. Scott-Smith writes:

Evidence from the 1960s demonstrated that a less protein-rich, more balanced diet could cure kwashiorkor equally well, and by the 1970s a number of other causes for the disease were suggested – even today, the details of kwashiorkor are still not fully understood.

Had scientists paid closer attention to the name ‘kwashiorkor’ they may have come to this realisation sooner. It is a disease of poverty where adults are unable to provide weaned children with adequate nutrition. As a result, its solution is distressingly simple: better and more food.

If there is any indicator of the extent of poverty in the platinum belt, then it is the fact that children suffer from kwashiorkor. While Lonmin has ploughed some of its profits back into communities surrounding the mines – opening schools and running feeding schemes, for example – it remains the case that mineworkers and their families are still desperately poor.

Keith Breckenridge argues that the wealth generated by workers operating in exceptionally dangerous conditions is channelled largely to a small group of beneficiaries. He adds:

Under the current arrangements in the platinum belt there is almost no movement of resources from mining to the wider problem of maintaining the physical and emotional well-being of the general population working in the mines. Mine managers have retreated from maintaining order and health in the hostels, and they have ceded control over the key human resource questions – employment and housing – to union officials and their allies. Like foreign shareholders and local royalty owners, these union leaders, using their monopoly over jobs and housing, have tapped into the demand for employment to enrich themselves (often at the expense of the working and living conditions of union members). Local government – caught between the mines and the prerogatives of tribal authorities – has all but abandoned the project of regulating the living spaces around the mines.

Where once miners were coralled into the prison-like conditions of single-sex hostels where their food, accommodation, and other expenses were covered by mining companies, now meagre housing allowances are meant to support these workers and their families in the otherwise badly provisioned and serviced towns and villages in the platinum belt. Salaries tend to go straight to pay interest on loans granted by micro lenders, charging exorbitant interest rates.

As the incidences of kwashiorkor reported to Lonmin suggest, these men were not earning enough to feed themselves and their children. While under cross examination at the Farlam Commission of Inquiry into the Marikana massacre, Cyril Ramaphosa – current Deputy President and Lonmin board member who had emailed the then-Police Minister, demanding an end to the workers’ strike – remarked:

The responsibility has to be collective. As a nation, we should dip our heads and accept that we failed the people of Marikana, particularly the families, the workers, and those that died.

I dispute the ‘we,’ Mr Deputy President.

Further Reading

Keith Breckenridge, ‘Marikana and the Limits of Biopolitics: Themes in the Recent Scholarship of South African Mining,’ Africa, vol. 84 (2014), pp. 151-161.

Keith Breckenridge, ‘Revenge of the Commons: The Crisis in the South African Mining Industry,’ History Workshop Journal Blog, 5 November 2012.

Tangerine and Cinnamon by Sarah Duff is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Reblogged this on Life's Journeys Unfolding.