Small Things

The institute at which I’m based regularly hosts book launches, seminars, and workshops. This past week was particularly busy. There was a daylong workshop and I attended two launches and four seminars, one of them the first in a major series connecting academics and policy makers.

All this meant that I didn’t do terribly much cooking, relying instead on the buffets provided at these events. These ranged from middling wine and taco chips, to nice beer and miniature versions of comfort food. I tend to give anything containing fish and eggs and most forms of meat a wide berth (I’ve long experience with dodgy seminar food), and stay with the vegetables. I’ve written before how important food is to academic gatherings: it helps to force otherwise shy graduate students to interact with senior staff; it pushes along conversations, facilitates discussion.

The said, terrible conference food can create a kind of solidarity. At a conference in Gaborone last year, colleagues and I almost wept with joy at the discovery of a nearby supermarket that sold yogurt and other alternatives to the almost inedible lunches and dinners we were served. On the other end of the scale, I spent quite a lot of time at events at the London Review Bookshop as a PhD student because their snacks were so substantial I could easily eat supper there.

These kind of finger foods are now so ubiquitous at academic – and other – events that it’s easy to assume that it was ever thus. It is certainly true that many cuisines have invented small snacks to fill the void between meals, and to accompany alcoholic drinks: canapés – fish, meat, and other toppings on pieces of toasted bread – were developed in the French court during the eighteenth century. Similarly, tapas, crostini, and even sandwiches evolved as bread-based snacks to eat alongside beer and wine.

There is a difference, though, between finger food and snack food: the former is usually eaten as a light meal alongside whatever’s being served to drink, and often at formal occasions. Snack food – sometimes renamed street food today – exists for eating on the run: quick bites taken in a busy day. (Contemporary bemoaning of the fact that people tend to snack or ‘graze’ all day instead of eating three ‘proper’ meals ignores the fact that the idea of eating only during the morning, at midday, and in the evening, is a relatively recent one.)

The finger food that we’re familiar with today has a relatively short history, and emerged in the United States in the 1920s. During Prohibition (1920-1933), owners of speakeasies and hosts of private parties serving alcohol illegally, began to offer patrons and guests small snacks to eat alongside their cocktails. These needed to be small – easily held in one hand and eaten in a couple of bites – and enticing: speakeasies could drive up their profits by charging extra for food.

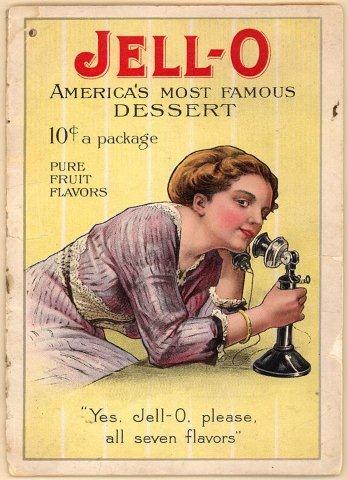

But as Sylvia Lovegren notes, the popularity of finger food spread beyond places where alcohol was served. Middle-class American kitchens and eating habits were being transformed by the greater availability of relatively cheap canned and bottled products, and new appliances, like refrigerators and freezers. The rise of what she calls ‘dainty food’ was in many ways a reaction against the heavy, elaborate cooking of the turn of the century. Dainty food consisted of salads in jelly (not aspic), of vegetables and meat mixed with mayonnaise and arranged in hollowed-out melons or iceberg lettuces (a cultivar developed specifically to withstand long journeys from farms to greengrocers), and of very sweet, tiny puddings. The marshmallow was ubiquitous on party menus.

This food was, quite obviously, gendered too. As more women entered the kitchen in the absence of cheap servant labour, the slew of recipe books – many of them published by food companies and appliance manufacturers – and magazines aimed at these new housewives, emphasised the ease of making this food, and also that it was small and ‘ladylike’. Being based on processed food made in factories described as hygienic and using ‘scientific’ processes, this was food that was neither messy to make, nor messy to eat. Jelly out of a packet took a few hours to set, while making aspic from cows’ hooves – as cooks would have done only a few years previously – was a time-consuming, labour-intensive, and smelly process.

Although finger food may have been popularised by the fashion for cocktail parties during the 1920s – a worldwide phenomenon – they became part of the way we eat because of how kitchen technologies changed, and how women’s position in households altered. For young women with relatively little knowledge of food or cooking, they were an attractive, apparently scientific, and easy way of feeding a horde of guests.

Sources

Sylvia Lovegren, Fashionable Food: Seven Decades of Food Fads (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

Jessamyn Neuhaus, ‘The Way to a Man’s Heart: Gender Roles, Domestic Ideology, and Cookbooks in the 1950s,’ Journal of Social History, vol. 32, no. 3 (Spring 1999), pp. 529-555.

Tangerine and Cinnamon by Sarah Duff is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

On academic eating, you may be interested in this website:

http://academic-breakfast.tumblr.com/

It’s fantastic – thanks!