Not Foodies, but Food

In this week’s Mail and Guardian, Mandy de Waal describes a spat between established food journalists and South Africa’s increasing ranks of food bloggers. This tension between professional food writers and amateurs who write simply for pleasure isn’t particular to South Africa: in the United States, Pete Wells was notoriously rude about food bloggers, and Giles Coren of the Times referred to them as ‘pale, flabby’ and ‘wankerish’ (although, presumably, he didn’t include his food blogging wife in this description). In a sense, it was inevitable that the same argument would boil over in South Africa.

The focus of De Waal’s piece is on charges of unprofessionalism levelled at the new media, as well as on the amusing pettiness of food bloggery in this country – particularly in the Cape, where most of the country’s top restaurants are situated. I’d like to pick up on one point that she makes in passing. She quotes JP Rossouw, author of the eponymous restaurant guides:

Yes, [food blogs] are playful and fun, but the mistake we make is to attach too much importance to what essentially is candyfloss.

Exactly. One of the most comical features of many food bloggers is their incredible self importance. (De Waal mentions one author who refused to accept food served to her at a special lunch at Reuben’s Restaurant because it came on a large platter and not individual portions. Good grief.) They dress up recipes and accounts of meals as moments of incredible profundity – moments which demonstrate the authors’ connectedness with the local restaurant in-crowd, insider knowledge of international culinary trends, and superior ability to understand the ‘real’ significance of food. These blogs are, in other words, manifestations of food snobbery.

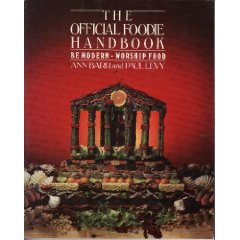

It’s little wonder, then, that so many food bloggers describe themselves as ‘foodies’. This term has travelled a long way since it was coined by Ann Barr and Paul Levy in the early 1980s. Now it’s usually taken to mean a love and enthusiasm for eating, cooking, and finding interesting new ingredients. It’s shorter, and sounds less pretentious, than ‘food lover’. I think that many food bloggers use the term in this sense. But it was originally meant to describe a kind of food snobbery. Stephen Bayley explains:

We have, in the past, had epicures, gourmets and gastronomes, but today’s foodie is rather different. A foodie is someone whose interest in comestibles is not only ardent, but also exquisitely self-conscious. Foodies treat their asparagus kettles not as mere utensils, but as badges of honour in the nagging battle for self-identity.

The same goes for ingredients: while once we had only Sarson’s non-brewed condiment to put on our chips, the foodie store cupboard now contains vinegars with genealogies, rare and costly vintages of balsamic, fruit vinegars made with herbs, herb vinegars infused with fruit to put on their pommes allumettes. A defining foodie product is verjuice, or what used to be known as filthy cooking wine. And foodies explore more than the palate: they hunt and collect restaurants, too.

Barr and Levy’s The Official Foodie Handbook (1984) walked an uneasy line between being a spoof of a new middle-class trend (and this could only be a fashion followed by those wealthy enough to buy the exotic and expensive ingredients and meals demanded by foodie-ism) and a guide to it. Angela Carter commented that it was best to understand the Foodie Handbook within the context of the other Handbooks published by Harpers & Queen:

the original appears to be The Official Preppy Handbook, published in the USA in the early days of the first Reagan Presidency. This slim volume was a light-hearted check-list of the attributes of the North American upper middle class, so light-hearted it gave the impression it did not have a heart at all. The entire tone was most carefully judged: a mixture of contempt for and condescension towards the objects of its scrutiny, a tone which contrived to reassure the socially aspiring that emulation of their betters was a game that might legitimately be played hard just because it could not be taken seriously, so that snobbery involved no moral compromise.

The book was an ill-disguised celebration of the snobbery it affected to mock and, under its thinly ironic surface, was nothing more nor less than an etiquette manual for a class newly emergent under Reaganomics. It instructed the nouveaux riches in the habits and manners of the vieux riches so that they could pass undetected amongst them. It sold like hot cakes.

In other words, the books began a process which has recently been completed: satirising while simultaneously approving, even celebrating, snobbery.

I realise that many food bloggers don’t know about the etymology of ‘foodie’ and don’t mean to use it to mean what it did originally. And I have nothing at all against what most food bloggers do: sharing recipes, advice, and useful information about food and cooking. They do what cooks and food enthusiasts have been doing for hundreds of years. A greater flow and availability of information about food can only be a good thing.

But I do object very, very strongly to the foodies – in Barr and Levy’s terms – of the internet who use their blogs and, occasionally, presence on social media to write about food, and good food, as the exclusive preserve of those who have the knowledge, sensitivity, and right social connections truly to appreciate what is worth eating. A few years ago, the BBC aired a fantastic comedy series called Posh Nosh. Starring Arabella Weir and Richard E. Grant as a social-climbing (her) and upper middle-class (him) pair of foodies, the series lampooned the deep, moral seriousness of foodie-ism. As Grant’s character says in the first episode (and I urge you to watch the series – most of it seems to be available on YouTube), ‘Food is beauty. And beauty is food’:

One of the useful things about foodies is that it takes very little to show how ridiculous they and their pretentions are.

Food, then, is like cars, furniture, or clothes: it’s another way of signifying people’s class status and social positioning. Of course, we’ve used food to do this for hundreds of years. But the difference with foodie-ism is that it attaches a moral value to eating in a particular way. Foodies confuse this snobbery with doing and being good. For foodies, knowing about and eating good food is a badge not only of class status and social and cultural sophistication, but also of moral superiority. Roasting organic purple-sprouting broccoli and then drizzling it with an estate-origin extra virgin olive oil signifies the foodie’s commitment to being green and supporting small, artisan producers. This dish is a manifestation of why that foodie is a Good Person.

It’s for this reason that I object so strongly to foodie-ism. Not only does it mystify cooking and eating, and elevate them to experiences that can only be appreciately properly by appropriately trained foodies, but it judges those who – for whatever reason – eat less well than themselves. Foodies, then, don’t really care that much about food and eating.

The subtitle of the Official Foodie Handbook is ‘Be Modern – Worship Food’. By elevating – or fetishising – food to the level of something which needs to be worshipped, foodies no longer think of food as food – as nourishment which we all need to consume – but as something which is simply an indicator of status and value. They don’t aim to inform and educate about food, nor do they work towards making good, wholesome food more widely available. They simply congratulate themselves on eating well. In a time when food prices are sky high – and look likely to remain that way for the forseeable future – and the planet’s diet is looking worse than ever, it strikes me that to ignore these crises while claiming to be interested in food and to enjoy eating, is deeply hypocritical.

Tangerine and Cinnamon by Sarah Duff is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Tangerine and Cinnamon by Sarah Duff is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Share this:

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window) Pinterest

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window) Tumblr

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window) Email

- Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X

- Click to print (Opens in new window) Print

Related

Trackbacks & Pingbacks

- Food Futures « Tangerine and Cinnamon

- Foodie Pseudery (1) « Tangerine and Cinnamon

- Psychofood « Tangerine and Cinnamon

- Fed Up | Tangerine and Cinnamon

Foodism is not always about elevating food worship into an indicator of status, often it really is just a shared happy obsession. Of course I could spend my every waking hour improving the lot of the world, but that would be a pretty joyless existence. Sensuality has it’s place, even in a world where many don’t have that option, and it doesn’t even have to be unsustainable.

Exactly – and my point is that foodIE-ism is about the worship of food.

There IS another person on the planet who watched Posh Nosh! The perfect, wickedly precise julienne job on foodie-ism.

Thanks for another deeply enjoyable post – your blog now goes straight into Instapaper to spend time on later and follow the links. (I have also shamelessly pilfered your Twitter follows for interesting lefties, greenies and, erm, foodies).

It’s GLORIOUS. I wish the Beeb would commission another series.

And thanks! I’m so glad you enjoyed it. Clearly you are a man of rare taste and discernment.

A great post and an interesting topic. I recently read the book ‘The man who ate the world’ by Jay Rayner and the subject of food elitism comes up. Its perhaps endemic in most cultures (in England, Japan, America etc) apart (as he comments) from in France, where good food is something that is insisted upon, enjoyed and eaten by people at all levels of society.

Part of my philosophy and why I started my food blog was a very simple interest in sharing my love of food. In many ways to hopefully break down barriers regarding some of the elitism and certainly demystify. Unfortunately very often the best food comes with a big price tag and thus enjoyed mainly by the higher end of the spectrum.

I agree that the bigger issues around food and health should not be ignored and at the end of the day food is just food.

PS: the women who refused the food at the Reubens lunch was in fact a professional writer and not a food blogger, I sat at the same table as her, which is simply an action of a person with bad manners vs the bahviour of a whole group of people as has been intimated in the press lately

Thanks! So glad you enjoyed it. Actually I disagree with Rayner about France. People will find ways of being snobs about food (as they will about most things) regardless of where they live. David Lebovitz’s blog has some gems of French food snobbery.

Your point about food and eating healthily is a really important one.

Goodness me – I had no idea it was a hack who was so badly behaved. Worse and worse.